Crisis instrument central bank swaps

In a recent article, Perry Mehrling drew attention to the global network of central bank swaps:

“In the last few weeks, the ECB has been drawing on its liquidity swap line with the Fed, first $308 million for a week, then $658 million for a week, and last week back down to $358 million. What’s that about?

It’s not such a large amount. Bank of Japan borrowed more in the past, $810 million in March and $1528 million in January. But the question then repeats, what was that about?

Both of these drawings are part of the new set of central bank swap lines linking what I call the C6: the Fed, ECB, Bank of Japan, Bank of England, Swiss National Bank, and Bank of Canada. On October 31, 2013 these lines were made permanent and unlimited … Ever since then I have had a slide in my powerpoints saying “Forget the G7, Watch the C6.””

So, what is going on here?

As Perry Mehrling noted, central bank swaps are in some ways similar to a standard commercial foreign exchange swap. But, there are also differences.

A commercial swap is an exchange of two currencies for a specific period with a reversal of that exchange at the end of the period. It consists either of a combination of a spot and a forward leg or of two forward trades with different maturities. The cost is the swap rate, which is the difference between spot and forward rate (or between the two forward rates involved). This in turn is equal to the interest-rate differential for a given term. The swap rate is always paid to the holder of the currency with the lower interest rate.

Swaps can be used either to avoid or take foreign exchange risk. For example, a company which is expecting a payment in a foreign currency at some future date may wish to lock in the current exchange rate by buying the respective amount spot and at the same time selling it forward to the day when it may settle the trade with the incoming payment. On the other side, as I wrote elsewhere, swaps can be used to prolong an open position exposed to foreign exchange risk in search of a currency profit.

Central bank swaps differ from these kinds of transactions in several respects.

First of all, they are instruments of monetary policy. They are based on official reciprocal arrangements of swap lines which allow a future exchange of one currency for another under certain conditions:

“Swaps lines between central banks enable the receiving central bank … to obtain foreign currency liquidity from the issuing central bank. Such agreements have been part of central banks’ set of monetary policy instruments for decades. Their primary use was originally to temporarily affect the domestic liquidity situation when other instruments would not serve the purpose or to temporarily and indirectly influence foreign exchange rates. In addition, foreign exchange swaps have been used to allow central banks to acquire foreign exchange to fund interventions.” (ECB)

Furthermore, central bank swaps differ from commercial swaps in that they may require prior notice and may have a maximum duration. (See for this and the following, for example, the documents in the Federal Reserve Central Bank Liquidity Swaps Arrangements Archive).

In addition, as Perry Mehrling observed, “the forward rate in the contract is usually exactly the same as the current spot exchange rate. This means that central banks are never in the position of realizing profits or losses from the swap. … Usual practice has been for the party who draws on the line to pay interest on the line at some penalty rate. Thus the May 9, 2010 swap agreement between the Fed and ECB called for the ECB to pay the USD Overnight Index Swap Rate plus 100 basis points on its dollar borrowing, and the Fed to pay nothing on its euro borrowing. In effect, the ECB was simply borrowing dollars at the discount window, like any other bank, but with its own monetary liability serving as collateral instead of some financial asset.”

There are risks. The Council on Foreign Relations wrote: “While the terms of swap agreements are designed to protect both central banks involved in the swap from losses owing to fluctuations in currency values, there is some risk that a central bank will refuse, or be unable, to honor the terms of the agreement. For this reason, lending through currency swaps is a meaningful sign of trust between governments.”

Central bank swaps have a long history. The ECB mentioned that until the 1990s, the Fed maintained an extensive network of foreign exchange swap lines with various central banks and the BIS. (The swap lines with central banks of euro area countries were discontinued with the introduction of the single currency in 1999.)

Initially, swap lines were mainly intended to increase central banks’ financial scope to fight a currency crisis. While, in principle, a central bank’s means to counter an appreciation of the domestic currency – which it can issue itself– is unlimited, its ability to cope with an ongoing devaluation is determined by the level of foreign reserves. The idea behind swap lines was to alleviate this problem as they widen the available pool of funds.

In a market with a $5.3 trillion estimated average daily trading volume, however, the concept has never been tested in earnest. Not even the wide dollar/euro swings in recent years have tempted the authorities in Europe and the US to intervene on a scale that would have required the use of a swap line. Rather it is as Perry Mehrling observed that “smaller sums are becoming a routine way of handling the normal stresses and strains of world funding flows.”

In a market with a $5.3 trillion estimated average daily trading volume, however, the concept has never been tested in earnest. Not even the wide dollar/euro swings in recent years have tempted the authorities in Europe and the US to intervene on a scale that would have required the use of a swap line. Rather it is as Perry Mehrling observed that “smaller sums are becoming a routine way of handling the normal stresses and strains of world funding flows.”

There has been one exception, however. The table below shows the amounts borrowed from the Fed by other C6 members at selected dates. The series dates back to May 2010. With the exception of smaller drawings by the SNB in 2011 and 2012, only the ECB and – to a lesser extent – the Bank of Japan have been making use of Fed swap lines so far. The selection here draws attention to the one occasion where this use was extensive. It started in September 2011 and lasted until summer 2013.

In the course of the European debt crisis, during this time, the ECB borrowed dollars from the Fed and lent them on to banks in Europe who had dollar liquidity needs and were unable, as Perry Mehrling wrote, ”for whatever reason, to access dollar funding in the open market, or only at a premium … higher than the ECB charges”. At its peak in February 2012, the ECB had $89,698 million outstanding swaps with the Fed. This and the BOJ’s $20,473 million in January 2012 dwarf the sums mentioned by Perry Mehrling for both central banks in 2015.

In the second half of 2012, the situation began to calm down as “banks’ actions to address the ESRB’s recommendations, the progress in the euro area in terms of fiscal consolidation, economic recovery and structural reforms, and the continuous provision of unlimited US dollar funding all contributed to the normalization of the US dollar funding markets for euro area banks. Demand for the regular US dollar tenders dropped throughout 2012 and remained very limited in 2013.” (ECB: Experience with Foreign Currency Liquidity-providing Central Bank Swaps)

In the second half of 2012, the situation began to calm down as “banks’ actions to address the ESRB’s recommendations, the progress in the euro area in terms of fiscal consolidation, economic recovery and structural reforms, and the continuous provision of unlimited US dollar funding all contributed to the normalization of the US dollar funding markets for euro area banks. Demand for the regular US dollar tenders dropped throughout 2012 and remained very limited in 2013.” (ECB: Experience with Foreign Currency Liquidity-providing Central Bank Swaps)

The incident indicates a shift in focus of the use of central bank swap lines in major markets. Instead of providing liquidity to economies “when other instruments would not serve the purpose”, and intervening to dampen currency fluctuations, helping out domestic banks came to the fore:

“Since the onset of the financial crisis in 2007, bilateral central bank swap lines allowing the provision of foreign currency to local counterparties have become an important tool of central bank international cooperation to prevent systemic risk and limit contagion across major currencies. The design and calibration of the operations used by the ECB to provide foreign currency liquidity to domestic banks helped to achieve the key objectives of the swap lines and calmed markets and funding concerns during the crisis … (ECB).”

The reference to systemic risk and contagion can hardly disguise the fact that here the Fed was de facto “bailing out” European banks, as critics remarked.

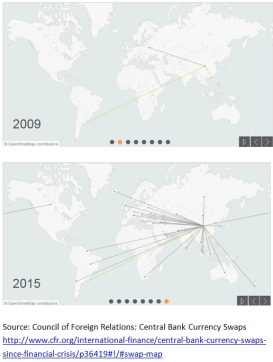

Since the financial crisis of 2007, central banks around the world have entered into a multitude of bilateral currency swap agreements with one another. The Council on Foreign Relations traced their history:

Since the financial crisis of 2007, central banks around the world have entered into a multitude of bilateral currency swap agreements with one another. The Council on Foreign Relations traced their history:

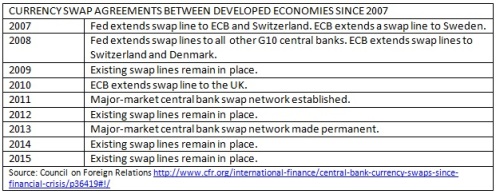

“On December 12, 2007, the Federal Reserve extended swap lines to the European Central Bank (ECB) and Swiss National Bank (SNB). European bank demand for dollars had been pushing up, and creating accentuated volatility in, U.S. dollar interest rates. The swap lines were intended “to address elevated pressures in short-term funding markets,” and to do so without the Fed having to fund foreign banks directly [my emphasis].

On September 16, 2008, two days after the collapse of Lehman Brothers, the Federal Reserve Open Market Committee (FOMC) gave the foreign currency subcommittee the power “to enter into swap agreements with the foreign central banks as needed to address strains in money markets in other jurisdictions.” This enabled the subcommittee to extend swap lines to other central banks and to expand the size of the existing swap lines, without the need for the full FOMC to vote on it. … Two days after the subcommittee was granted this power, the Fed expanded the size of the swap lines with the ECB and SNB, and extended three new swap lines, to Canada, the United Kingdom (UK), and Japan. On September 24, 2008, further swap lines were extended to Australia, Denmark, Norway, and Sweden. On October 28, 2008, a swap line was extended to New Zealand.

The ECB established swap lines with Sweden in December 2007, the SNB and Denmark in October 2008, and the Bank of England in December 2010. The euro area, Sweden, Denmark, and the UK had relatively low foreign exchange reserves going into the crisis, owing to the costs involved in holding reserves and the belief that there was little likelihood that more would be needed in the foreseeable future. However, banks in these countries borrowed large sums in foreign currencies in the years leading up to the crisis. When it became difficult for them to borrow funds in 2008, they turned to their central banks, reserves of which proved insufficient to meet the unanticipated demand. The ECB swap lines were therefore called into use in 2009 to provide Sweden and Denmark euros with which to top up their foreign exchange reserves, and the swap line with the SNB was called upon to provide the ECB with Swiss francs. The swap line with the Bank of England was put in place as a precautionary measure to ensure that the Central Bank of Ireland, which is part of the Eurosystem, had access to pounds sterling, but it has never been used. Since 2007, Sweden and Denmark have more than doubled their foreign exchange reserves, the UK has doubled its reserves, and the euro area has increased its reserves by 20 percent.

The ECB established swap lines with Sweden in December 2007, the SNB and Denmark in October 2008, and the Bank of England in December 2010. The euro area, Sweden, Denmark, and the UK had relatively low foreign exchange reserves going into the crisis, owing to the costs involved in holding reserves and the belief that there was little likelihood that more would be needed in the foreseeable future. However, banks in these countries borrowed large sums in foreign currencies in the years leading up to the crisis. When it became difficult for them to borrow funds in 2008, they turned to their central banks, reserves of which proved insufficient to meet the unanticipated demand. The ECB swap lines were therefore called into use in 2009 to provide Sweden and Denmark euros with which to top up their foreign exchange reserves, and the swap line with the SNB was called upon to provide the ECB with Swiss francs. The swap line with the Bank of England was put in place as a precautionary measure to ensure that the Central Bank of Ireland, which is part of the Eurosystem, had access to pounds sterling, but it has never been used. Since 2007, Sweden and Denmark have more than doubled their foreign exchange reserves, the UK has doubled its reserves, and the euro area has increased its reserves by 20 percent.

In 2011, the Bank of Canada, Bank of England, European Central Bank, Bank of Japan, Federal Reserve, and Swiss National Bank announced that they had established a network of swap lines that would allow any of the central banks to provide liquidity to their respective domestic banks in any of the other central banks’ currencies. In October 2013, they agreed to leave the swap lines in place as a backstop indefinitely”.

Perry Mehrling commented: “For lack of a world central bank, we have a network of central bank liquidity swaps.”

Other swap agreements worth mentioning include the Chiang Mai initiative which was established after the 1997–98 Asian financial crisis. It started as a network of bilateral currency swap agreements between the members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), China, South Korea, and Japan. Here is once more the Council on Foreign Relations:

Other swap agreements worth mentioning include the Chiang Mai initiative which was established after the 1997–98 Asian financial crisis. It started as a network of bilateral currency swap agreements between the members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), China, South Korea, and Japan. Here is once more the Council on Foreign Relations:

“In 2010, the Chiang Mai Initiative (CMI) was multilateralized, meaning that it was converted from a network of bilateral agreements between countries into one single agreement, the Chiang Mai Initiative Multilateralization (CMIM). A surveillance unit, the ASEAN+3 Macroeconomic Research Office (AMRO), was created to monitor member economies for signs of emerging risks and to provide analysis of countries requesting funds from the CMIM, much as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) does for its member countries. The fourteen countries participating in the CMIM agreed to a certain financial contribution and were thereafter entitled to borrow a multiple of this, ranging from 0.5 for China and Japan to five for Vietnam, Cambodia, Myanmar, Brunei, and Laos. In 2014, the size of the agreement was doubled from $120 billion to $240 billion, and the amount a country could access without being on an IMF program was raised from 20 percent to 30 percent.

These swap lines have never actually been used. Even during the financial crisis, when Korea was drawing as much as $16.4 billion from its swap line with the Federal Reserve, neither Korea nor any other country that was party to these agreements used them to obtain foreign currency. While the amounts available through Chiang Mai were potentially large enough to significantly augment a country’s reserves, IMF conditionality (for borrowing beyond 20 percent of a country’s quota) was a major deterrent to using Chiang Mai funds; in contrast, borrowing the full amount available through the Fed’s swap lines did not require any kind of IMF program.”

The Council on Foreign Relations also drew attention to another network of bilateral currency swap agreements in the region, and this one has been used extensively due to special circumstances:

“Since 2009, China has signed bilateral currency swap agreements with thirty-two counterparties. The stated intention of these swaps is to support trade and investment and to promote the international use of renminbi.

Broadly, China limits the amount of renminbi available to settle trade, and the swaps have been used to obtain renminbi after these limits have been reached. In October 2010, the Hong Kong Monetary Authority and the People’s Bank of China (PBoC) swapped 20 billion yuan (about $3 billion) to enable companies in Hong Kong to settle renminbi trade with the mainland. In 2014, China used its swap line with Korea to obtain 400 million won (about $400,000). The won were then lent on to a commercial bank in China, which used them to provide trade financing for payment of imports from Korea.

In addition to using the swaps to facilitate trade in renminbi, China is also using the swap lines to provide loans to Argentina in order to bolster the country’s foreign exchange reserves. In October 2014, a source at the Central Bank of Argentina reportedly told Telam, the Argentine national news agency, that the renminbi Argentina receives through the swap could be exchanged into other currencies. Argentina has had difficulty borrowing dollars on international markets since it defaulted on its debt in July and has faced shortages on a range of imported goods as a result.”

China’s swap lines 2009 and 2015

Given the size of world financial and foreign exchange markets these days, the original idea of establishing central bank swap lines to widen the pool of funds to fight a currency crisis has hardly any chances for success. As impressive as the figures quoted by Perry Mehrling look at first glance, they would never suffice to stem the flood of currency flight and massive speculation.

But, as the above examples show, the nature of central bank swaps as an instrument of monetary policy has fundamentally changed in recent years.

Central banks use swap lines

– to strengthen political ties,

– pursue reserve-currency ambitions,

– undertake rescue operations for domestic banks,

– to keep together a currency union which is in danger of falling apart,

– and bail out foreign banks to mitigate the risk of contagion.

It is in this context that the word “unlimited” in the C6 agreement gives rise to concern.

—–

Links

ECB: Experience with Foreign Currency Liquidity-providing Central Bank Swaps

Federal Reserve Foreign Exchange Swap Agreements

Federal Reserve press release May 11, 2010

Central Bank Liquidity Swaps Arrangements Archive

Transcript of the Federal Open Market Committee Conference Call of December 6, 2007

Meeting of the Federal Open Market Committee on September 16, 2008